1890-1927: Founding and Beginnings

As Chicago prepared for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, two orators and educators wisely chose the Windy City as the home of a new public speaking college.

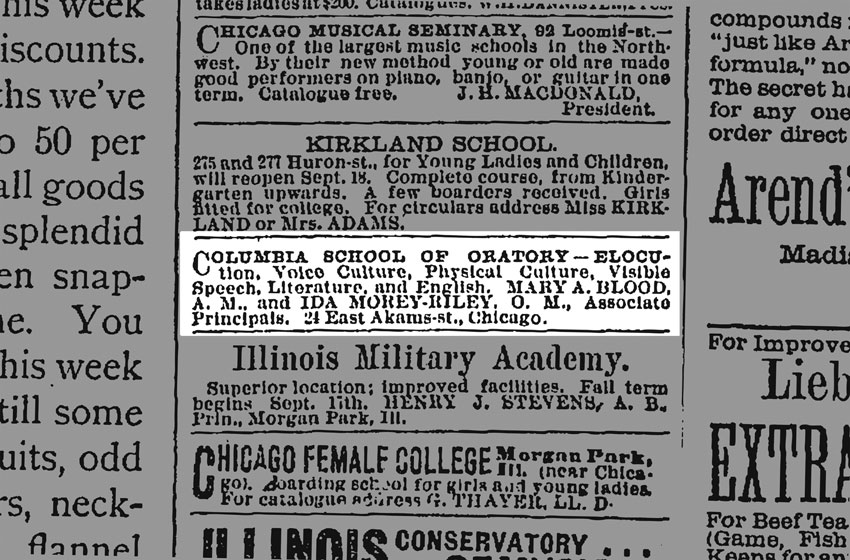

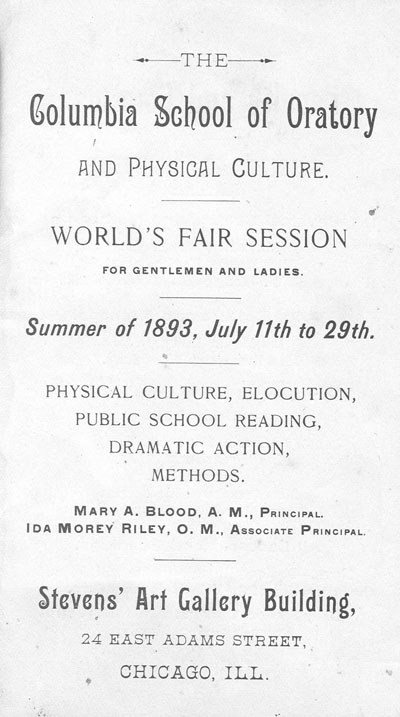

From the ashes of the 1871 Great Chicago Fire rose skyscrapers, the elevated train and a vibrant culture shaped in the world’s fifth largest city—setting the stage for the humble beginnings of what is now Columbia College Chicago. On August 25, 1890, a small and unassuming ad appeared in the pages of the Chicago Tribune. At just five lines, the description of the Columbia School of Oratory was brief and to the point: “Elocution, Voice Culture, Physical Culture, Visible Speech, Literature and English.” The principals were listed as Mary Blood and Ida Morey Riley.

Blood and Riley met at State Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, where Blood was a visiting professor. Both women saw a great demand for public speaking education. In 1890, they founded the Columbia School of Oratory, taking the name from the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition, which would be the largest public attraction the world had ever seen. The gigantic fair’s opening day wasn’t until 1893, but with three years to go, Chicago was already preparing. After all, the six-month- long celebration of Christopher Columbus landing in America would bring global attention to the city.

On August 25, 1890, a small and unassuming ad appeared in the pages of the Chicago Tribune.

Through this period of growth and celebration, Columbia took root. The Stevens Art Gallery Building at 24 E. Adams St. housed Columbia’s first classrooms. There, in the heart of the bustling business district, Blood and Riley taught English, literature and public speaking. Columbia shared the building with other ventures including an art gallery, a store, and spaces for musicians, hat makers, artists and fashion designers. The school offered two-year diplomas, bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees to budding orators and teachers of expression, reading and debate. Columbia handed out nine diplomas at the first graduation ceremony in 1892—eight of them to women.

Through this period of growth and celebration, Columbia took root. The Stevens Art Gallery Building at 24 E. Adams St. housed Columbia’s first classrooms. There, in the heart of the bustling business district, Blood and Riley taught English, literature and public speaking. Columbia shared the building with other ventures including an art gallery, a store, and spaces for musicians, hat makers, artists and fashion designers. The school offered two-year diplomas, bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees to budding orators and teachers of expression, reading and debate. Columbia handed out nine diplomas at the first graduation ceremony in 1892—eight of them to women.

By 1905, school officials had incorporated the college as a not-for-profit institution renamed the Columbia College of Expression and created its first board of trustees. The school also moved to Steinway Hall, 64 E. Van Buren St., where it occupied the entire seventh floor. The 1905 course catalog described the building as “located in the very heart of the downtown educational center. … The rooms set apart for this College are light, airy and commodious. … They include a beautiful hall, recitation rooms, library, reception room, offices, etc., all arranged with studied care, and furnished with every modern convenience.”

In 1916, the college established a dedicated Department of Public Speaking with alumnus R.E. Pattison Kline as its dean. Columbia also offered a series of correspondence public speaking courses with lessons and homework to be completed and mailed back for feedback from college instructors. Students could also obtain a certificate of training for the Chautauqua Circuit, a traveling education and entertainment series of the era (and a sort of precursor to today’s TED conferences). Columbia students and alumni joined the circuit, as did faculty and college presidents, who spoke to crowds in towns across the United States. The movement, which President Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America,” was popular until the birth of radio.

The school offered two-year diplomas, bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees to budding orators and teachers of expression, reading and debate.

Although Columbia was secular and coeducational from the start, Blood’s religious convictions influenced the curriculum. The college offered Bible-reading classes and strongly encouraged weekly church attendance to promote “sterling Christian character.” The Evanston-based Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), of which Blood was an active member, endorsed Columbia as a central training school for temperance activists. Even though this ideological foundation has largely changed, the school’s early motto, “Esse quam videri” (“To be rather than to seem”) is as vital today as it was more than a century ago.

Mary Blood: President 1890-1927

An 1897 newsletter from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) praised “gentle, forceful” Mary Blood’s public speaking. When she read the story of Absalom at the organization’s “Pleasant Sunday Afternoons” event, the audience paid attention: “Men who would have scorned a ‘Bible story’ from other lips hung spellbound on her words. … Indeed, it was to us all as if we had heard it for the first time.”

An 1897 newsletter from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) praised “gentle, forceful” Mary Blood’s public speaking. When she read the story of Absalom at the organization’s “Pleasant Sunday Afternoons” event, the audience paid attention: “Men who would have scorned a ‘Bible story’ from other lips hung spellbound on her words. … Indeed, it was to us all as if we had heard it for the first time.”

Before founding Columbia School of Oratory in 1890, New Hampshire-born Blood taught on the faculty at Boston’s Monroe College of Oratory (now Emerson College). During her tenure at Monroe, she served as a visiting professor at the State Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, where she met fellow teacher Ida Morey Riley. Blood encouraged Riley to study at Emerson, and afterward the two women moved to Chicago to open the school that would grow into today’s Columbia College Chicago.

While serving as Columbia’s co-president, Blood taught the Emerson System of Physical Culture at Columbia and was even a member of a physical culture exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. She taught people to use their entire bodies in public speaking to “let their light shine through.” To Blood and her students, the body was an instrument of God.

The unmarried Blood taught elocution at a time when women were learning to use their voices, and Columbia opened at a significant time in women’s history.

Physical culture was also promoted by the WCTU, of which Blood was a longtime member. Though the WCTU’s main focus was evangelical Christianity and support of Prohibition, the organization also campaigned for women’s suffrage and inspired a generation of women to get involved in political life. The unmarried Blood taught elocution at a time when women were learning to use their voices, and Columbia opened at a significant time in women’s history. In 1889, social activist Jane Addams opened Chicago’s Hull House, offering a hub for social change. Women suffragists continued fighting for the right to vote— though the 19th Amendment wouldn’t be passed until 1919. In this period of political change, Blood encouraged her students to enter the public sphere as elocutionists, performers and teachers.

In 1927, at age 76, Blood died in the 120 E. Pearson St. building at the college she founded. Many alumni showed up for her funeral, which was held on campus. She is buried in her hometown of Hollis, New Hampshire, where her epitaph reads: “She was one of the founders and for 37 years the president of the Columbia College of Expression in Chicago, Illinois.”

Ida Morey Riley: President 1890-1901

Little is known about Columbia co-founder Ida Morey Riley, who was born in 1856 and raised in Iowa. After the death of her husband when she was just 23 years old, she focused on her teaching career, becoming principal of the same public school she attended in her youth.

Little is known about Columbia co-founder Ida Morey Riley, who was born in 1856 and raised in Iowa. After the death of her husband when she was just 23 years old, she focused on her teaching career, becoming principal of the same public school she attended in her youth.

While teaching at the State Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, in 1887, she met Mary Blood, a visiting professor from the Emerson School of Oratory (now Emerson College). At Blood’s urging, Riley moved to Boston and studied at the Emerson School. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Oration in 1889 and a master’s degree in Oration in 1890, she joined Blood in Chicago, where the two women established the Columbia School of Oratory in 1890.

“… the helpful interest which she exercised in behalf of each and all, will be held in sacred and grateful remembrance.”

In addition to serving as Columbia’s co-president, Riley also served as secretary of the National Association of Elocutionists and was a member of its board of directors until her death after a brief illness in 1901. An obituary in Werner’s Magazine remarked that “her thirst for knowledge was early a marked characteristic,” and that she was beloved by her students, who drew up a resolution that stated: “… the high esteem in which we held her [makes] it fitting that we record our love and appreciation … her kindness of manner and nobleness of spirit, her patience and fidelity … the helpful interest which she exercised in behalf of each and all, will be held in sacred and grateful remembrance.”

Home Sweet Home

Where Columbia lived from 1890 to 1927

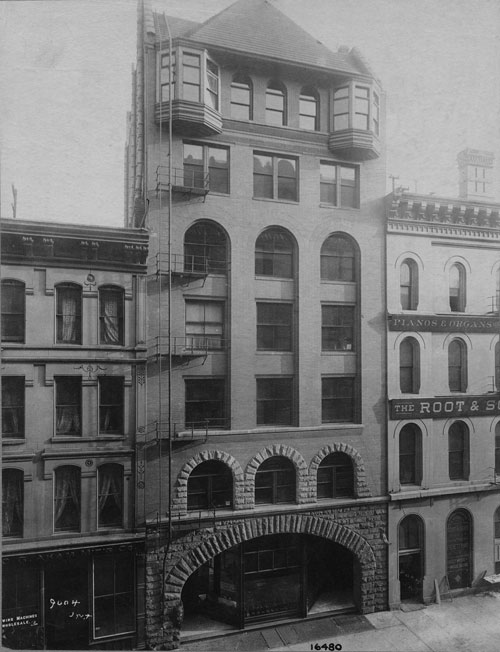

Stevens Art Gallery Building 24 E. Adams St.

Occupied: 1890–1895

Housed: Entire campus

Trivia: This was Columbia School of Oratory’s first home, which also offered space to an art gallery; a store; and offices for artists, musicians and fashion designers.

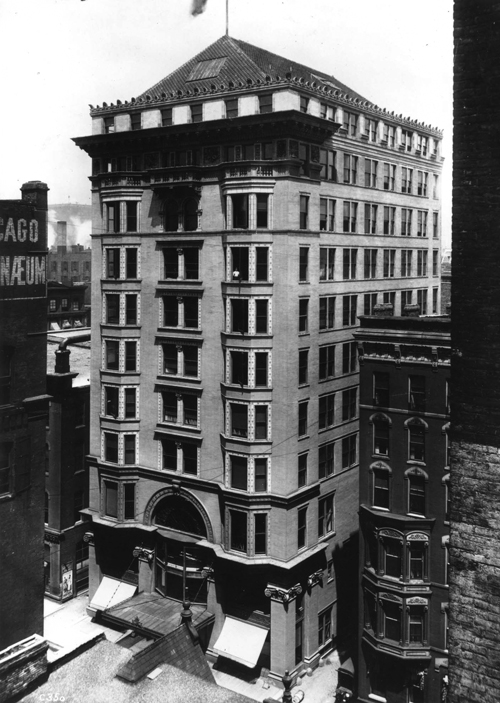

Steinway Hall 64 E. Van Buren St.

Occupied: 1895–1916

Housed: Entire campus

Trivia: According to the 1905–1906 college catalog, founders Mary Blood and Ida Morey Riley helped design the building’s seventh floor, which Columbia occupied. The building was razed in 1970 to make way for the CNA Center.

3358 S. Michigan Ave.

Occupied: 1916–1925

Housed: Entire campus, dormitory for women

Trivia: The mansion was built for meatpacking mogul Charles Libby and rented to Columbia by his widow.

Dining Room

Only female students lived in the mansion; male students rented rooms in nearby boarding houses.

120 E. Pearson St.

Occupied: 1925–1927

Housed: Entire campus

Trivia: When Mary Blood died in 1927, her funeral services were held at this location. The building was demolished, and the location is now a Topshop clothing store.

Second to None

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 became a growing city’s claim to fame

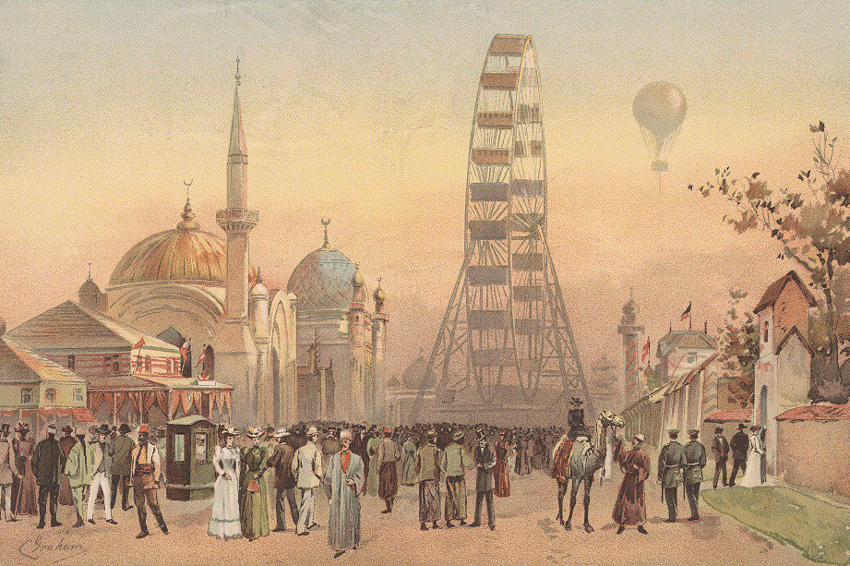

The historic World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 spread over 630 acres on Chicago’s South Side.

In the years leading up to the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicago buzzed with preparations and excitement. The fair celebrated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus landing in the New World. When Mary Blood and Ida Morey Riley arrived in Chicago, they were so inspired by the upcoming historic fair that they named their new educational venture the Columbia School of Oratory.

The World’s Columbian Exposition was the largest public attraction the world had ever seen. Staggering in size and scope, the fair spanned 630 acres on Chicago’s South Side in Jackson Park and attracted more than 27 million visitors over six months. Renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted created the layout, and the main fairgrounds, dubbed the “White City,” featured more than 200 buildings designed by the leading architects of the day, overseen by architect Daniel Burnham. Forty-six countries and nearly every state in the nation contributed exhibits. The fair also highlighted new inventions and manufactured goods, introducing the world to the Ferris Wheel, Cracker Jack and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer.

After outbidding New York to host the fair, Chicago—which was a serious economic and industrial power in the midst of a population boom—could shine on a world stage. At the time, East Coast elites thought of Chicago as a crime-ridden backwater; the fair’s organizers were determined to overcome this reputation with a beautiful, edifying exposition and cement the city’s place as a cultural capital. (The New York press dubbed Chicago the “Windy City” due to the fair promoters’ relentless boosterism.) As the fairgrounds rose on the lakefront, Blood and Riley knew the event would bring massive crowds to the city and provide a platform for trained public speakers. Blood even served on a committee for an exhibition of physical culture at the fair that espoused fitness of the body and mind (also key concepts in the school’s curriculum). Coursework during the summer of 1893 was designed with the fairgoer in mind, and tuition included a personal tour of the city for visiting students. While all Columbia students had the opportunity to attend the fair, one 1893 graduate had special involvement: Grace Griswold Hall recited passages from select works at the fair’s Woman’s Building on October 10.

1890s: Oral Bocock

A 1935 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune featured the appointment of Oral Bocock (married name: Mrs. Edward J. Lehman) as the head of the Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs. While noting her dedication to “school budgets and club conferences,” the Trib also predicted she’d “never lose her girlish thrill in acquiring a new dress or an autumn hat.” The 1895 graduate of Columbia spent a decade as a teacher, dramatic coach and public reader.

1900s: Emanuel D. Schonberger

Though Emanuel D. Schonberger would eventually focus on theatre, he penned Columbia’s alumni song as a student in 1904. “Here’s a health to our dear alma mater, here’s a pledge of devotion and truth / May she glow in our hearts bright and brighter as our school days recede with our youth,” begins the song that still appears in the Columbia student handbook. The song is set to the tune of “Marcha Real,” the national anthem of Spain.

Hold forever, Columbia, thy station / Fling thy true colors free to the wind —Columbia’s Alumni Song

Schonberger moved west after his 1909 graduation, becoming a professor of public speaking and the director of the Dakota Playmakers at the University of North Dakota. He also wrote a book that helped others take the stage. Fundamentals of Play Production hit the streets in 1912 and is still available for purchase.

1910s: Jean Williams

The Chautauqua Circuit, a popular adult education movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, dispersed entertainment and culture throughout American communities with assemblies of speakers, teachers, musicians and preachers, often gathered under a tent. Jean Williams, a 1915 alumna from Alabama and part of the Columbian Entertainers, hit the road as a Chautauqua reading performer.

The Chautauqua Circuit, a popular adult education movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, dispersed entertainment and culture throughout American communities with assemblies of speakers, teachers, musicians and preachers, often gathered under a tent. Jean Williams, a 1915 alumna from Alabama and part of the Columbian Entertainers, hit the road as a Chautauqua reading performer.

The Anniston (Alabama) Evening Star praised her stage presence and clarity of voice, declaring, “Her poise was excellent, her articulation and expression perfect.”

1920s: Dorothy Peterson

Dorothy Peterson’s breakthrough role in the movie Mothers Cry, a 1930 talkie, called for the 29-year-old stage actress to age nearly 30 years throughout the film. The 1920 Columbia graduate nailed the character and was subsequently typecast into maternal roles that marked a 34-year acting career. Peterson appeared in 83 films in all, ultimately mothering the most famous of all child stars, Shirley Temple, in 1947’s That Hagen Girl.

Dorothy Peterson’s breakthrough role in the movie Mothers Cry, a 1930 talkie, called for the 29-year-old stage actress to age nearly 30 years throughout the film. The 1920 Columbia graduate nailed the character and was subsequently typecast into maternal roles that marked a 34-year acting career. Peterson appeared in 83 films in all, ultimately mothering the most famous of all child stars, Shirley Temple, in 1947’s That Hagen Girl.

1920s: Mildred Carlson Ahlgren

In the 1950s, Mildred Carlson Ahlgren took the communications skills she learned as a 1922 graduate of Columbia College of Expression to Washington D.C. and around the globe.

In the 1950s, Mildred Carlson Ahlgren took the communications skills she learned as a 1922 graduate of Columbia College of Expression to Washington D.C. and around the globe.

An outspoken woman from Indiana Harbor, Ahlgren became president of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) in 1952, heading an organization of more than 5 million women and advocating for women’s rights and global goodwill in Washington D.C. After her presidency ended, she remained with GFWC as a public relations director and consultant and led groups of women in goodwill tours around the world, including in South America and Russia.

In the 1950s, Mildred Carlson Ahlgren took the communications skills she learned at Columbia College of Expression to Washington D.C. and around the globe.

Ahlgren earned many distinctions during her career. President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed her a member of the White House Conference on Education, and she was the first American woman to earn the Royal Order of the Vasa from the king of Sweden for contributions to cultural life.

Then and Now: Hands On, Minds On

Then: Mottos such as “Hands on, minds on” and “Theory never made an artist” informed Columbia’s immersive teaching style from its founding. An early logo from 1905 proudly states “Learn to Do by Doing” above the college’s name.

Now: From the very start, students are actively involved in their education: First-day film students are handed a camera and told to go shoot, and journalism students hit the street immediately to start reporting. Columbia’s workshop method and faculty of working professionals are cornerstones of the college, building its reputation as a place to learn practical skills and build a body of work from day one.