This week thesis-year student Jillian Bruschera co-taught a workshop with Laura Anderson Barbata, an artist from Mexico City whose work, Homecoming for Julia: Language and Labor, was recently installed as part of the current Social Paper exhibition at the Center for Book and Paper Arts.

Known around the world as the “bear woman”, Julia Pastrana’s thick-hair covered body, enlarged gums and lips were the resulting effects of two rare diseases: generalized hypertrichosis lanuginose and gingival hyperplasia. Her life was largely about her looks. She spent her waking life as a sort of traveling circus show freak, but the story doesn’t end there. After Pastrana died from complications of childbirth, her lifeless body underwent a process of taxidermy so that her husband could continue to exhibit, and profit from, Pastrana’s body. This all happened in the mid-1800s. In the years that followed, her cadaver spent time in and out of forensic and medial institutes. Her remains were studied and further abused, eventually housed in a basement utility closet at the University of Oslo.

In 2005, artist Laura Anderson Barbata began a petition for Pastrana’s repatriation. Her goal was to bring Pastrana back to her homeland of Sinaloa, Mexico for a proper burial. After years of petitioning with the authorities, Barbata succeeded — in February 2013, a wopping 153 years after her death, Pastrana was finally put to rest.

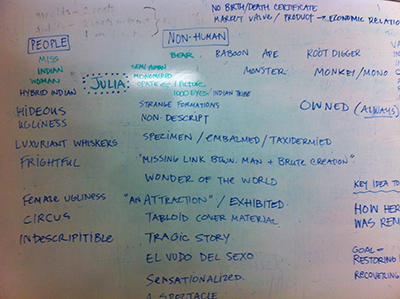

The workshop participants spent the first part of the workshop talking about oppressive language in the media, beginning with examples specific to Julia Pastrana’s life. Playbills, advertisements, tabloids, and so fourth, referred to Julia as a “monster”, “nondescript”, “hideous” and “semi-human”, to name a few.

Conversation focused on how her humanity was removed. In making connections to themes of human trafficking, slavery, abuse and exploitation, they discovered that Pastrana’s story is ultimately one about human rights. The ultimate goal of the workshop was to transform this language and to restore, or recover, her identity. Through papermaking they could reconnect her to humanity, collectively making a series of paper flags and flowers in her honor. Some of this artwork will travel back to Julia’s tombstone in Mexico, and some pieces were buried in the snow of the Papermaker’s Garden.