Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace?

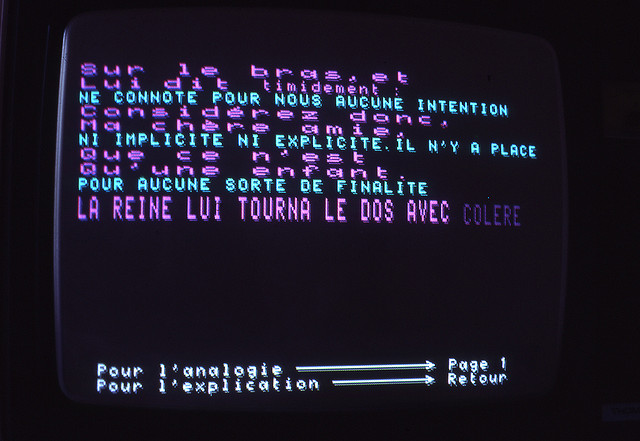

Roy Ascott. Minitel, Paris, Les Immateriaux

This past week in Art as Discourse, we read Roy Ascott‘s 1990 essay “Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace?“. According to Ascott, there is, or at least, there could be.

Ascott says that telematics, “involves the technology of interaction among human beings and between the human mind and artificial systems of intelligence and perception. Within this telematic embrace arises the question of content.” He suggests that there are, amongst the critics of art involving computers, “deep seated fears of the machine coming to dominate the human will and of a technological formalism erasing human content and values.”

Through this collaborative artwork between human and machine, Ascott believes that that the observer becomes a participator because the work has the “capacity to engage the intellect, emotions, and sensibility of the observer.” He says that a classical communications theory has the “artist as sender and therefore the originator of meaning, the artist as creator and owner of images and ideas, the artist as controller of context and content.” This theory is what gives rise to the critic—the idea that there is one correct answer to the ideas and/or questions which the author of the work presents or asks, and it is the work of the highest intellect that is able to decipher this riddle.

Ascott also finds this telematic embrace in what he calls the new literary criticism, which includes philosophy and social theory in its practice. He says, “This sunrise of uncertainty, of a joyous dance of meaning between layers of genre and metaphoric systems, this unfolding tissue woven of a multiplicity of visual codes and cultural imaginations was also the initial promise of the postmodern project before it disappeared into the domain of social theory…”

These ideas return me to Roland Barthes‘ “The Death of the Author.” Barthes suggests that the author or narrator must “enter into his own death” and become a mediator, medium, or shaman who relates the story to the one reading (or viewing) the work. He says that “to give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing.” He goes on to say that “the reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination… the birth of the reader must be a the cost of the death of the Author.”

Many of the readings of the past weeks for this course (including Fluxus and Relational Aesthetics) seem to point in the same direction of the death of the capital “A” in Artist, Author, etc. The telematic embrace makes the author a collaborator. The connectivity of cyberspace creates a flux in meaning. In the words of Ascott, “ The emerging new order of art is that of interactivity of ‘dispersed authorship’; the canon is one of contingency and uncertainty… [N]etworking provides the very infrastructure for spiritual interchange that could lead the harmonization and creative development of the whole planet… Love is contained in this total embrace…”

Zapp & Roger, Computer Love

Zapp & Roger, Computer Love