Peter the Great

Columbia’s first Academy Award winner fought for screen credits for sound editors, mentored Steven Spielberg and later reinvented himself as a versatile writer.

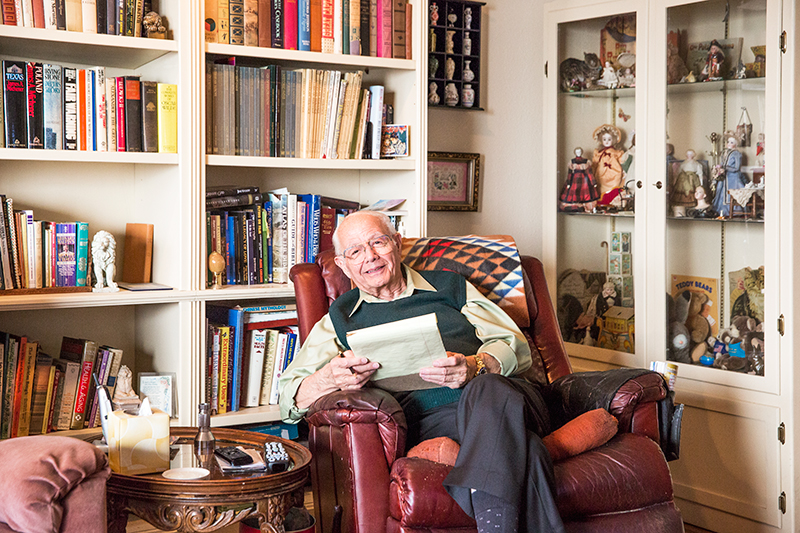

“I knew nothing about what I was getting into,” says Peter Berkos (BA ’51) as he reflects on the beginning of a career that spanned half a century. The 92-year-old Columbia College alum—Oscar winner, Hollywood veteran, novelist—humbly maintains that “most of the things that I did, as far as my career, I fell into. I just was in the right place at the right time.”

After serving in the U.S. Army Air Force, Berkos enrolled at Columbia on the GI Bill. “It was a lot smaller than it is today,” Berkos says. “At that time [1948], the entire college was in the Fine Arts Building [410 S. Michigan Ave.]. Television was so new we were using a box on a tripod as a camera and a toilet paper roll as a lens,” he jokes.

Berkos credits the college’s working professionals with molding his direction. Drama professor and mentor Aline Neff pushed him toward directing, which he did for stage, radio and TV. Another instructor, actor/director Gilbert Fergusen, “talked me out of dropping out in my first year,” Berkos says.

Shortly after graduation, the eager filmmaker decamped for Los Angeles along with his wife Sally Ann, also an alum, and two of his classmates, Sam Reynolds and Sam Berland, who would become lifelong colleagues and friends. “We decided to go to Hollywood, where films were being made,” he says. “We packed up and came out here. We were four Columbia students, working together.”

Berkos began as a storeroom clerk at Universal Studios, and spent nearly three years working his way up to the production offices, and then editorial. He especially enjoyed working one-on-one with actors and directors on re-recording dialogue through a process called automatic dialogue replacement (ADR). In the late ’50s, Berkos spent a whole day with Hollywood legend Orson Welles working as a sound editor on Touch of Evil (1958). Eventually, he worked up to the role of supervising editor. “My job was to create the sound effects, and I usually had no less than five people assembling the soundtracks,” he says.

In the mid-’60s, Berkos spent two months mentoring an aspiring young filmmaker who wanted to understand sound editing, Steven Spielberg. “He turned out to be the most enthusiastic film man I’ve ever met,” Berkos says. “He’d be there in the morning, waiting for me to open my editing room. He never wanted to go to lunch.”

In 1963, Berkos became president of the Motion Picture Sound Editors, where he began a long fight for sound editors’ membership in the film and television academies—as well as for screen credits for sound effects editors. Back then, giving screen credit to sound editors wasn’t just uncommon—it was unheard of. Berkos spent 12 arduous years bargaining with the studio system for sound field recognition. He himself never received screen credit until the late 1970s, and it wasn’t until the ’80s that sound editing became an annual Academy Award category.

“In 1996, Berkos received a lifetime achievement award from the Motion Picture Sound Editors—the very organization that he helped build.”

Robert Wise’s disaster epic The Hindenburg cemented Berkos’ place in cinema history. He won a Special Achievement Academy Award for Sound Effects in 1976 for his work on the film—becoming the first Columbia College graduate to win an Oscar.

“When I first saw the film in its rough state, I said to my assistant, ‘If we handle this right, there’s an Oscar in it,’” Berkos says. But after six or seven attempts to create the effects, he still couldn’t find the perfect noise for the creaks and groans of the Hindenburg’s aluminum skeleton.

“I went back to my room and sat in front of my bench,” Berkos says, “and I leaned back to fold my arms across my chest, and all of a sudden the chair I was sitting on—squeak! I started moving back and forth squeak, squeak! I called my assistant, George, and said, ‘Book me a studio right now!’”

The recorded sounds of the noisy chair ended up in the movie. “You never know where you’re going to get sounds from,” Berkos says. “It’s creative, and that’s the part of the job that I liked best. It paid the most in satisfaction.”

Before he retired in 1987, Berkos worked on more than 300 films and 1,000 television episodes. He remains active in the Motion Picture Sound Editors and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. (He’s a voting member for the Oscars.) For many years, Berkos taught seminars at film schools as part of an Academy educational outreach program.

In 1996, Berkos received a lifetime achievement award from the Motion Picture Sound Editors—the very organization that he helped build. “I was complaining to Sally one time—all the stuff I did for these sound editors, they don’t even remember, they don’t know,” he says with a laugh. “I was crying in my milk. The very next day, I got a call that I was getting the award.”

Berkos speaks of his wife, who passed away in 2000, often and fondly. He compiled and self-published Reflections and Memoirs of Sally Ann Berkos, a collection of his late wife’s writings. Then he reinvented himself as a novelist. He followed up his debut sci-fi novel, Tpito the Third Twin (2007), with The Double Double Cross (2013), a mystery set in the post-production department at a movie studio. He aims to publish a third book, Stage Fright, in late 2015.

To Berkos, storytelling is an art that transcends mediums. “My writing is very visual,” he says. “In the movies, when a director wants you to feel a certain emotion, he might do it with music. In writing, I do it with words.” —Audrey Michelle Mast (BA ’00)